|

Lecture

Notes 3 Economics of the Environment and

Natural Resources/Economics of Sustainability K Foster,

CCNY, Spring 2011 |

|

|

Short Review

of Production

Production Externalities

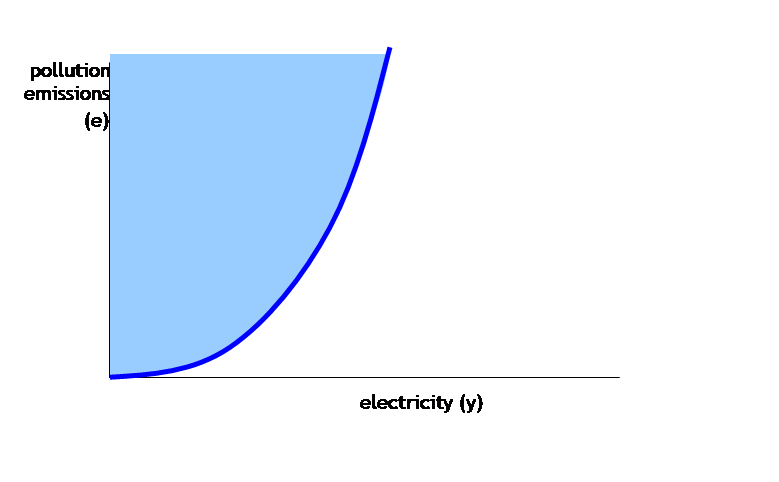

In the

simplest case, we can examine a firm making a single private (rival and

excludable) output and incidentally a single public (nonrival

and nonexcludable) output (for now, we assume that

this public good is disliked). An easy

example could be a power plant which makes electricity and pollution. (Actually a variety of sorts of pollution,

which affect different groups of people: carbon, mercury, NOX, and sulphur dioxide are the main ones.)

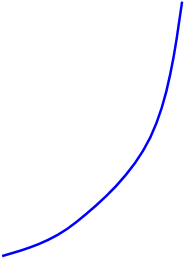

In this case

the production can be shown as being like a production possibility frontier but

with the pollution increasing along with the output, something like:

The firm can

choose any combination of electicity & pollution

within the light blue area. Clearly,

however, the firm would be foolish to choose a point inside the area; the

points at the dark blue line are efficient.

These are the production possibility frontier. They are efficient because there is no way to

increase the output of electricity without also increasing the output of

pollution (this would not be true for points in the interior).

|

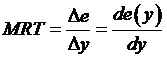

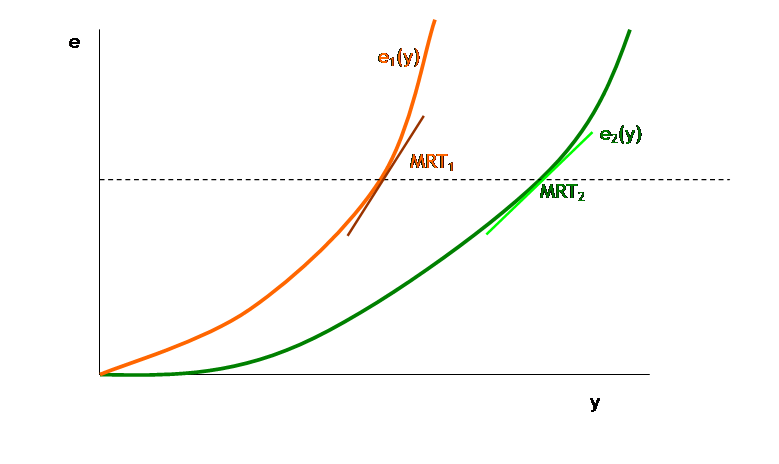

At any point along the frontier of production

possibilities, we can define the marginal rate of transformation as the

change in output of pollution per change in output of electricity – the slope

of the line. With the notation of e

for pollution emissions and y for the output of the firm, the marginal rate

of transformation, MRT, here is |

|

This

interpretation of the choice along the production possibility frontier as

representing a choice of marginal rate of transformation allows us to compare

firms and make statements about the relative efficiency.

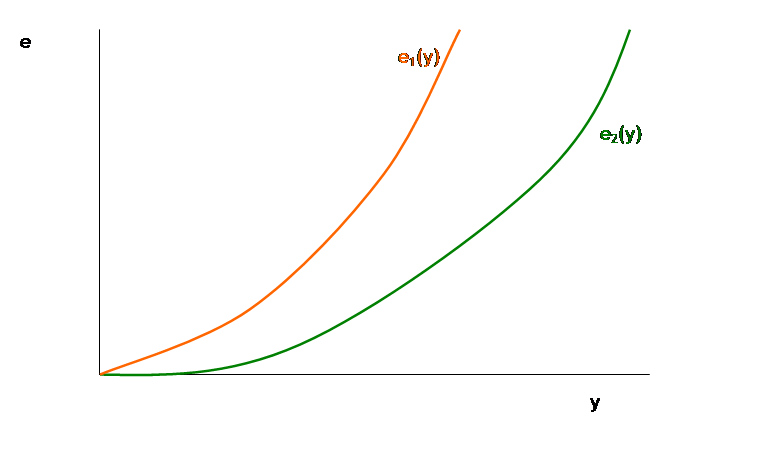

Suppose

there are two firms which, for some reason or another, have different emissions

per unit of output. Graphically this

would be represented as:

If they each

produced the same amount of emissions, they would of course be able to generate

different output levels, but their marginal rates of transformation would also

be different.

Clearly the

marginal rate of transformation of firm 2 is lower than the marginal rate of

transformation of firm 1. This means

that when firm 2 generates one more unit of output, it creates fewer emissions

than firm 1 does. This means that, if

firm 2 were to make one more unit of output while firm 1 made one unit less –

keeping the total output of the two firms at the same level, the increase in

emissions from the second firm would be (in absolute value) less than the

decrease in emissions from the first firm.

So total emissions would be smaller even though the output was kept

constant.

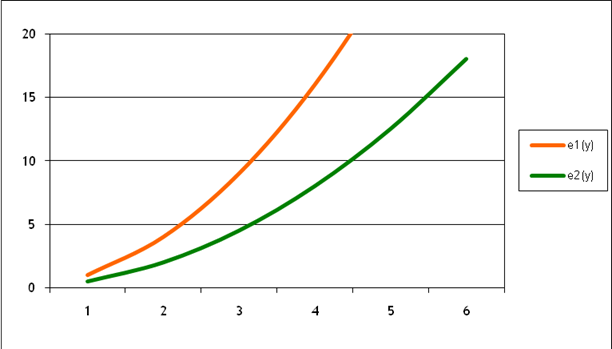

Consider a

simple numerical example, where ![]() but

but ![]() . This is plotted as:

. This is plotted as:

If emissions

of each firm are 16, then firm 1 is producing 4 units of electricity while firm

2 is producing 5.66 units of electricity.

If firm 2 produced one more unit of electricity its emissions would rise

to 22.16, an increase of 6.16. If firm 1

produced one less unit of electricity its emissions would fall to 9, a decrease

of 7. So if, instead of both firms

producing 16 units of emissions, firm 1 produced less and firm 2 produced more,

the overall production of electricity could remain constant while emissions

fall.

We can

continue this trade-off as long as the marginal rates of transformation are

unequal. It is only when the marginal

rates of transformation are equal that there will be a total efficient way of

getting the most output with the least amount of harmful emissions.

With a bit

more math, we can find the point where the MRTs for each firm will be equal.

|

Multiple Inputs |

|

|

It is rarely

quite appropriate to consider an output to be perfectly free, since there are

usually at least technological considerations.

So we can return to our usual marginal conditions, modified for the

firm. Consider a firm which has multiple

inputs available for making the output, each of which is useful and

productive. Each input has a cost (or

wage, if we extrapolate from the case of hiring workers) denoted wi.

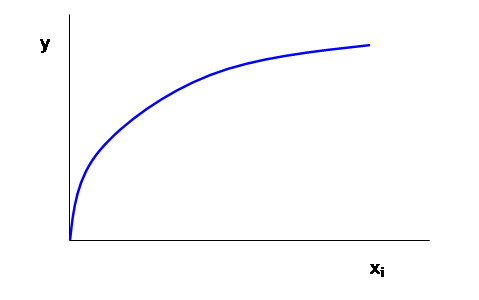

We typically

assume that, holding all of the other inputs constant, increases to just one

input will have a steadily-decreasing effect on increasing output. Graphically, this says that for each input, xi,

i=1, 2, … N, output, y, increases as:

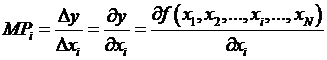

So, just as

with the consumer's diminishing marginal utility, the firm faces diminishing

marginal productivity. Just as with the

consumer, we define the production function as ![]() and the marginal product of each input as the

partial derivative,

and the marginal product of each input as the

partial derivative,  .

.

Also as

noted previously, the fact that each individual marginal product is diminishing

does not mean that production overall has diminishing returns to scale – where

'scale' refers to a case where all of the relevant inputs are increased. As a simple example, most offices generally

operate with each employee getting a computer.

Buying more computers without hiring more people might increase output,

but at a diminishing rate; the same would hold true for hiring more people

without getting more computers. But

getting more of both could allow the business to expand.

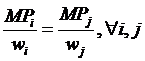

The firm

will maximize profits by choosing inputs such that (in the long run), the

ratios of ![]() ,

marginal productivity per cost of each input, is equal. The explanation should, by now, be typical:

if spending $1 more on input i increased output by more than spending $1 more

on input j, then the firm should decrease spending on input i while increasing

spending on input j. This will not only

allow the firm to make more output more cheaply but also tend to bring down the

marginal productivity of input j while increasing the marginal productivity of

input i, so that in equilibrium we have

,

marginal productivity per cost of each input, is equal. The explanation should, by now, be typical:

if spending $1 more on input i increased output by more than spending $1 more

on input j, then the firm should decrease spending on input i while increasing

spending on input j. This will not only

allow the firm to make more output more cheaply but also tend to bring down the

marginal productivity of input j while increasing the marginal productivity of

input i, so that in equilibrium we have  .

.

If one input

has a price which is increased (say, by some environmental regulation) then

this input will be used less. This is the substitution effect (see from

marginal condition).

There is

also a Scale Effect. As the cost of production

rises, the quantity of output demanded will fall, so fewer of all types of

input will be demanded.

Also, if

that input is non-excludable like polluted air or water, then other industries

could see their costs fall, so input used more – a different substitution

effect. Also a different scale effect.

Hicks-Marshall rules of Derived

Demand:

Demand

for input is more elastic when

1. technical substitution is easy

2. input cost share is high

3. input substitutes are supplied

elastically

4. demand for output is elastic

|

Social

Welfare |

|

|

It is

difficult enough to figure out how some impartial policy analyst might discover

these when social marginal cost or social marginal willingness to pay differs

from the private analogs, or what tax/subsidy would cure it. But that presumes that policymakers want to

maximize social surplus. To what extent

is that a good assumption?

First, how

exactly do we (ought we) define Sustainability?

Sustainability

and Sustainable Development

Principal

definition from the 1987 Brundtland Commission, Sustainable Development is

development that meets the needs of present generations without compromising

the ability of future generations to meet their own needs.

At the

American Museum of Natural History here in New York, the entrance rotunda has

the following words carved into the wall:

Nature

There is a delight in the hardy life of the

open.

There are no words that can tell the hidden

spirit of the wilderness, that can reveal its mystery, its melancholy and its

charm.

The nation behaves well if it treats the

natural resources as assets which it must turn over to the next generation

increased; and not impaired in value.

Conservation means development as much as it

does protection.

Theodore Roosevelt,

26th President of the United States (and the youngest ever) and also

a winner of Nobel Peace Prize, was a prominent advocate of conservation,

wilderness, and the AMNH. The last two

sentences can be seen as inconsistent and different varieties of

"sustainability" highlight one meaning or the other.

But Teddy Roosevelt's further quotes reveal

what he meant, "Conservation means development as much as it does

protection. I recognize the right and duty of this generation to develop and

use the natural resources of our land; but I do not recognize the right to

waste them, or to rob, by wasteful use, the generations that come after

us."

"Defenders

of the short-sighted men who in their greed and selfishness will, if permitted,

rob our country of half its charm by their reckless extermination of all useful

and beautiful wild things sometimes seek to champion them by saying the 'the

game belongs to the people.' So it does; and not merely to the people now

alive, but to the unborn people. The 'greatest good for the greatest number'

applies to the number within the womb of time, compared to which those now

alive form but an insignificant fraction. Our duty to the whole, including the

unborn generations, bids us restrain an unprincipled present-day minority from

wasting the heritage of these unborn generations. The movement for the

conservation of wild life and the larger movement for the conservation of all

our natural resources are essentially democratic in spirit, purpose, and

method." (Again, TR, A Book-Lover's

Holidays in the Open, 1916.)

Sustainability,

in whatever conception, is not straightforward to analyze within an economic

framework. We need to work out the

details of the definition farther.

|

From J.C.V. Pezzey & M.A. Toman,

(2008) "Sustainability and its Economic Interpretations," draft

chapter in Scarcity & Growth in the

New Millenium, ed R.U. Ayres, D. Simpson, & M.A. Toman. Big

question: can economy grow forever? Sustainability

in general is about equity between generations. Could either define it as equity of

outcomes (utility) or equity of opportunities. If look at outcome, then ask: can future

generations' utility continue without declining? If look at opportunity, then does wealth

never decline? Economic

problem: in many analyses we assume that people discount the future – find

the present discounted value of costs & benefits. We do this in analyzing investments by

private companies as well as governments.

But this discounting means that the welfare of future generations may

not be highly valued. Early

papers on economic growth provide boundaries of the problem. If there is a depletable natural resource,

then rational choice (discounting the future) by current generations implies

declining consumption over time. If,

on the other hand, technological growth is rapid enough, then the discounting

dilemma is solved: consumption can grow over time. The discounting dilemma shows that, even if

there are no externalities and every good is 'properly' priced, the economy

might still be unsustainable. First

question: so what? If every current

person likes the unsustainable path, then is there a moral basis to limit

current choice? If so, who will limit

current choices? Can we distinguish

between people acting as 'homo economicus' in markets but as 'Good Citizen'

in government? For a good review of

how important is economic growth to basic human welfare watch Hans Rosling's TED talk.

Do people

act rationally anyway? Do they discount

in that way? How do we deal with the

uncertainty inherent in some of these models?

No easy answers. Define

"Total Capital" as man-made capital (machines) plus human capital

(knowledge and expertise) plus natural capital (from the ecosystem). Write Often

distinguish between "strong" and "weak" sustainability -

weak sustainability implies that total capital does

not decline – but this can include cases where natural capital is used to

increase human or man-made capital.

This assumes that each type of capital is a perfect substitute for the

other. Also assumes that there is some

metric to convert all of the types of capital into a single unit (usually

present-value money) – otherwise how to add up machinery and university

degrees with coal fields, biodiversity, and clean water? -

strong sustainability implies that at least some component

of KN cannot fall below some critical value – there are threshold

effects. Precautionary Principle

follows. The Stern Report on Climate

Change ended up using this sort of argument to overcome the disagreements

about measurement that are inherent in the previous definition. -

Green Net National Product (GNNP) proposed to supplement GNP

to offset the depreciation of KNatural. Augmented National Income takes Green but

adds in technological progress.

Related is Genuine Savings,

which gives net investment after depreciation of all of the capital

amounts. So if Augmented National

Income is not rising then economy is unsustainable. -

if

economy has endogenous growth then this might be fast enough to overcome

environmental degradation -

Other

measures include "carbon footprint" (or other footprints) but these

lack clear justification |

Fundamental

question: if future generations will be much richer, then why must we now

sacrifice for them? Why should the poor

(us today) give to the rich (future generations)? Many countries and societies have developed

by first exploiting natural resources to get rich, then only later remediating

environmental harm (e.g. the

This

question of discounting arises often in policy disputes. We will come back to it (esp. in climate

change) but for now note that there is no simple answer.

Social Welfare

How can we,

as economists, say much about which outcomes are better than others, without

imposing our own particular ethics and morals?

Some outcomes might deliver high income inequality; some might constrain

inequality but with a lower average level of consumption. How can we say which is better?

I'll use the

general term "government" but this refers to any joint decision

making body. People get together to form

various organizations, which then promulgate rules that bind the members – any

of these organizations can be considered a 'government' from the view of social

welfare analysis. A building coop is a

'government' of a sort: it makes rules that (hopefully) help the people who

live there. Business Improvement

Districts join up local merchants. There

are unions and farmer marketing boards.

Then there are myriad levels of government in the conventional sense of

the word.

So how can a

government choose its goals? One of the

very minimal items that we might propose, is that we ought not to omit any

movements in allocations that are "Pareto improving." A Pareto improving trade gives something for

nothing – someone gets more utility without anyone else getting less

utility. Certainly these sorts of trades

ought to be made, right? So a

"Pareto optimal" economy has eliminated all of these possible trades

and has no more possibility of getting something for nothing.

This is what

kids do after getting Halloween candy: the one who likes chocolate best will

trade away the Starbursts and gummi bears to friends who like those more than

chocolate. Everyone wins.

The First

Welfare Theorem of Economics tells that every (frictionless) market equilibrium

is Pareto optimal. This tells us that,

based on the rather meager definition of "optimal" that we just gave,

that each market equilibrium meets this low criterion. This is nearly by definition: if there were

some trade that would make both parties happier, then they would make it in a

market economy (unless constrained by some friction; e.g. the whole Coase

discussion).

The Second

Welfare Theorem of Economics is more interesting. We just said that "Pareto optimal"

is a weak condition – a dictatorship where one person has nearly all of the

wealth, while the others toil in peonage, could be Pareto optimal. There are many possible Pareto optimal

equilibria. Suppose society had some

idea of which particular one it wanted – could a market economy get us

there? The Second Welfare Theorem tells

that every Pareto optimal allocation is a market equilibrium that started from

some initial endowment. So this makes a

lovely separation: if policymakers want to change which allocation they desire,

then they ought to change the initial endowments. The market system is not the reason for

inequalities or injustices – these mirror inequities in the original

allocations.

But, as we

said, there are many Pareto Optimal allocations – this is one consideration but

not the sole consideration. How can

society choose the "best" outcome?

The Second Welfare Theorem said that, if we had something to aim for, we

know how to hit it. But what do we aim

for?

Not every

Pareto Optimal allocation is very good: if we start from an aristocratic

society with 1% of people getting nearly all of the wealth while the other 99%

live at subsistence level, then there is no Pareto improvement that will help

the 99% who are peasants without taking something away from the aristocrats.

We would

like to have some sort of society utility function, analogous to an individual

utility function, so that we could use the rational choice apparatus to look at

social choices. Call this a "Social

Welfare Function," denoted W( ).

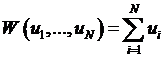

One idea for

a Social Welfare function is Utilitarianism, originally due to Jeremy Bentham,

which holds that we should just add up the utilities of the people in the

society, u1, … uN.

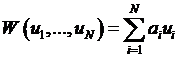

This sets

, or,

with slightly more generality,

, or,

with slightly more generality,

,

,

where the ai

are weights. This has problems, chiefly

being the impossibility of measurement, then the impositions upon human rights.

Remember

from our definitions of utility functions that these are just arbitrary

functions which represent preferences; any monotonically increasing function of

a utility function is itself a utility function. One person's utility of chocolate could be

1,000,000,000; another's could be -1 but we CANNOT conclude that the first

person likes chocolate better. How can

we compare happiness levels?

Then there

is the problem of human rights: if we believe that people have "certain

inalienable rights" then the utilitarian framework could justify, say,

selling one person into slavery if the money raised can make others happy

enough.

The

philosopher John Rawls proposed a minimax function,

![]() .

.

He propelled

this function by arguing that most people's definitions of a fair allocation

depend upon their knowledge of their own situation: someone who is intelligent

might happily agree to a society where smart people are well rewarded; someone

else with different advantages would argue for a different allocation. He proposed a thought experiment: what

allocation would be chosen, if the members of society could get together before

they knew what their own situation would be – whether they would be fortunate

or unlucky, healthy or sick, endowed with which talents? They would have to make a decision from

behind a "veil of ignorance" over their future endowments. Rawls argued that, from this perspective, a

person would give a great weight to the worst possibility – extreme risk

aversion – that a society with substantial inequality would not be appealing

because even a small chance of being utterly destitute would be too large. Therefore he proposed a minimax principle,

that every change in allocation, away from perfect equality, must help the

worst-off person. So he would allow

greater rewards to, say, doctors, in order to give them incentive to help the

sick and the most fragile members of society.

These social

welfare functions so far allow people's utilities to depend on anything and

everything. We might further restrict

that people's utilities depend only on their own consumptions, in which case we

would have a Bergson-Samuelson welfare function. But this is not generally realistic.

Rights-based

social welfare functions run into difficulties since these generally do not

allow tradeoffs – a slight diminution in some right might make everyone better

off. But rights-based are generally

"lexicographic" preferences where no positive benefit can possibly

compensate ("lexicographic" since Azzz is alphabetized before

Baaa). Yet different people have

different ideas about which rights are most important (in the US, the Supreme

Court must adjudicate when there are competing rights clashing). Many people voluntarily surrender certain

rights in order to gain other benefits (e.g. a coop or condo association

restricts property rights but is beneficial to property values); it is unclear

why a social welfare function should not do so.

We might

hope for an answer like "democracy".

But Ken Arrow (CCNY alumnus and Nobel Prize winner) showed that a

democracy does not guarantee rational orderings of choices.

Arrow's

Theorem states that if we desire:

- Completeness: The social welfare

function, W( ), is defined for all allocations,

- The social welfare function is

responsive to individual preferences,

- It is independent of irrelevant

alternatives (so if W(X)>W(Y) then adding a choice Z, if W(X)>W(Z),

does not change the original ordering) (like Transitivity)

- It is not an imposed dictatorship.

Then, if

there are more than 3 choices, there is NO POSSIBLE Social Welfare function can

be guaranteed to satisfy all four conditions.

People care

about justice and fairness and other considerations. Too many policy debates result from arguing

about proposals, where each side uses radically different definitions of these

terms – what do justice and fairness mean?

Economists have proposed some definitions.

The Second

Welfare Theorem got us focused upon initial allocations, so we might wonder if

that will help. Is a symmetric

distribution, where everyone gets exactly the same bundle of goods, fair? If people's utility functions are not

perfectly uniform then people will voluntarily trade among themselves, and we

will move away from perfect equality. Is

this desirable? Would someone envy

another person's allocation? Define envy that person i would prefer j's bundle

rather than her own. An allocation is equitable if none of the bundles are

envied. Define a fair allocation as one that is equitable and Pareto efficient (i.e.

nothing is wasted). Now it can be proved

that if society starts from a symmetric distribution then the outcome of market

trading will be fair, under this definition.

(But the symmetric outcome is not generally fair.)

From the

definitions of Pareto optimality, economists have often backed off to the

measure, "Possibly Pareto Improving" (or Potentially Pareto

Improving), to indicate that some policy could generate enough surplus to

compensate the losers and still leave the winners with something. For example, a policy that gave A $100 while

costing B just $40 would be Possibly Pareto Improving since A could compensate

B the $40 lost and A would still be $60 ahead.

This is the theory behind the general introductory lesson on Deadweight

Loss (DWL) – that social surplus could be increased by enough to compensate the

losers and still leave the winners ahead.

This sneaks

back a bit of Utilitarianism into the argument – now we're comparing utilities

but using the measure of dollars (marginal willingness to pay).

The problem

with "Possibly Pareto Improving" policies is obvious: the

"Possible" does not mean that it actually does occur! A policy that made Bill Gates $100 wealthier

while making the poorest person $90 poorer would likely be condemned by a

variety of social welfare functions. But

it is "Possibly Pareto

Improving" (even if it is improbable that it actually will be). Policymakers could justify a progressive tax

on the theory that it distributes some of these Possible Pareto gains from the

winners to the losers, but the connection between this progressive tax and

other policies is often lost.

The typical

economist's tool of "Cost-Benefit Analysis" has this same

shortcoming. This would add up the

marginal costs of some policy, add up the marginal benefits, and then make the

change if the benefits outweighed the costs.

Again this avoids all questions of who gets the net (social)

profit! Cost-Benefit Analysis is the

same as Possible Pareto Improving.