|

Basic Background Knowledge: Review of Economics Economics of the Environment and Natural Resources/ Economics of Sustainability K Foster, CCNY, Spring 2011 |

|

|

Although there are hard-core environmentalists who dispute it, as economists we must keep in mind that, to efficiently allocate scarce resources and to ensure that resources are most effectively used, markets are the best way that human ingenuity has been able to discover. This is true for most resources.

It is not true for all resources; this does not mean that no government intervention is ever justified. One of the objectives of this course is to figure out what institutional arrangements and structures allow markets to work, and which ones need to be improved. Where should government policy step in?

But a typical firm is run by managers who have a sharp incentive to cut costs: to limit the use of expensive inputs and to cut expenditures which do not directly impact customer satisfaction. Most consumers are looking for ways to cut their expenditures on items that do not bring adequate satisfaction.

So to begin, we will review basic economic theory about the allocation of scarce resources. Keep in mind that generally scarcity leads to a high price. An item with a high price will have lower demand from consumers. Items with high prices will not be used as intensively by producers. Both consumers and producers will cut back usage of the scarce resource in favor of cheaper resources.

1.

Economics

is the study of choice in a world of

scarcity (from intro text by Frank

& Bernanke yes, that Bernanke, who's now Fed Chair)

a. Some resources, which were once thought to be inexhaustible, are now known to be scarce; e.g. atmosphere (CO2 levels), clean air, fish in the sea

b.

Scarcity: No Free Lunch (TANSTAAFL) more of one thing means less of something

else. This applies to buying groceries

(more apples & fewer bananas) or choosing between car emissions &

safety (lighter cars mean better MPG & less emissions but also less safe in

accident).

c.

Choice: people are free agents who take

actions based on their own information and desires which do not necessarily match those of

policymakers. Usually assume people are

rational.

d. Rational people think on the margins (Mankiw's intro text)

e. Cost-Benefit Principle: it is rational to take action if and only if the extra benefits are as big as, or bigger than, the extra costs

i.

Economic Surplus = Extra Benefit Extra Cost.

So Cost-Benefit Principle can be restated as "Do actions with

nonnegative Economic Surplus".

ii. Opportunity Cost: The Extra Cost is the value of next-best alternative that must be given up to do something so Cost-Benefit means take an action only if it has nonnegative Economic Surplus; only if the extra Benefit exceeds the Opportunity Cost

f. If prices reflect true scarcity of all goods then people take proper account, not because of any moral feeling but to maximize profit. This goes back to Adam Smith's propositions and observations.

g. Environmental Economics is generally concerned with choices where the benefits and costs are shared even though the decision-making isn't necessarily

2. Production Possibility Frontier (PPF)

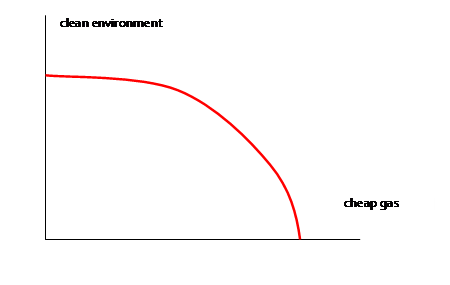

For example, politicians debate the tradeoff between cheap oil/gas (Drill Baby Drill!) and a clean environment. We can represent this tradeoff as

This shows that a society could have a completely clean pristine environment with zero cheap gas (where the PPF intersects the vertical axis). Or an utterly dirty environment and ultra-cheap gas (where the PPF intersects the horizontal axis). We would never want to be interior to the PPF, since this would mean that society could have more of both without any sacrifice. It is a frontier because anything beyond it is infeasible; anything within it is inefficient. Changing technology would allow the PPF to move outward so that society could have more of both.

The

opportunity cost is proportional to the slope of the PPF. The slope changes depending on how much

drilling or environment we already have.

If we already have a very clean environment with a low level of cheap

gas (at a point near the upper left of the PPF), then getting cleaner requires

a huge reduction in cheap gas to get only a small improvement in clean

environment the opportunity cost of the last bits of

environment is huge. Oppositely, if we

have a lot of cheap gas but little clean environment (we're on the lower

right), then cleaning up some means a small sacrifice of cheap gas (a low

opportunity cost). People can have

different preferences about what sacrifice is reasonable and so where on the

PPF the society ought to be.

Many examples: a lake can be used for recreation or reservoir of water supply; rainforest can be used for biodiversity or crops; land can be mined or left open; coast used for wind farm or beautiful scenery; etc.

3. Basics of Supply and Demand Curves

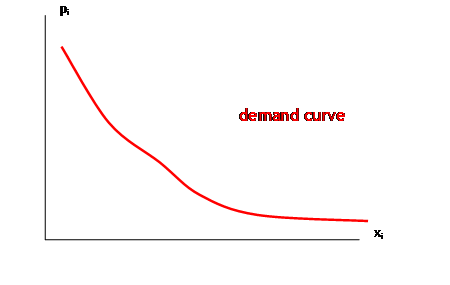

a. Demand Curve:

i. For each person: shows the extra benefit gained from consuming one more unit

ii. by Cost-Benefit Principle, if the extra benefit from consuming one more unit is greater than the price, then consume; if not then don't

iii. so Individual Demand Curve shows how many are purchased at any given price

iv. Individual Demand Curves are combined to get a market demand curve of how many would be purchased by all the people in the market at a given price (horizontal sum)

v. Depend on other factors than price (which shift the demand curve).

b. Supply Curve: opportunity cost of producing certain quantity of output.

i. If no fixed costs and no barriers to entry then firms produce at marginal cost

ii. Depend on other factors than price (which shift the supply curve).

c. Behavior of Markets: markets are a wonderful institution; we analyze with some assumptions

i. Depend on composition of good

ii. Depend on supply characteristics (how many firms, if there are fixed costs or other barriers to entry, rules & regulations and social norms

iii. property rights are completely known, specified & enforceable

iv. all property rights are exclusive (no externalities)

v. property rights are transferable

vi. items for sale have substitutes

vii. Commodities closely approximate these assumptions; other markets might be very far off (e.g. labor)

viii. What happens if demand is greater than supply? Vice versa?

d. Equilibrium: price and quantity that have no tendency for change

4. Some Common Mistakes

a.

Ignore

b. Fail to Ignore Sunk Costs (since they're no longer on the margin)

c. Fail to understand Average/Marginal Distinction

5. Analyzing Supply and Demand Curves

a. Consumer Surplus (CS)

i. You've surely had the experience: you go to a store to buy a particular item, ready to spend a certain amount of money. But surprise! You find it's on sale and you pay less than you expected. You've gotten Consumer Surplus. This did not come from the benevolence of the retailer (although they might try to convince you otherwise). This actually was a mistake by the retailer: they were targeting people whose choice could be influenced by the price reduction but accidentally got you too. You got a benefit from the fact that other people shop smart, with a keen eye on prices charged. You would have been willing to pay more, but because there's a market you paid less.

ii. Take all of the people who would have been willing to pay more than the actual market price and add up how much they each benefited. This total amount is CS: the area under the demand curve and above the market price. Consumers were willing to pay more than the market price; their marginal benefit from consuming those goods was above the price they paid, so they gained from this market.

iii. Examples: online websites, from eBay

to used cars, allow people to see the prices paid for other similar

products. Compare with buying a used car

without internet research must go to each dealer and haggle; don't know

if price is good or bad without substantial experience.

b. Producer Surplus (PS)

i.

Producers

also gain from a market. You are a

producer and seller of your own labor.

If you applied for a job and would have accepted a pretty low wage but you were surprised and the company offered

you a better wage than you would have accepted

then you got Producer Surplus. You benefit from the fact that there is a

market with competitors trying to buy the product.

ii. Find the difference between the lowest price that the producer would have accepted (supply curve) and the actual price received. Add these all up for PS: the area above the supply curve and below the price is Producer Surplus. Producers were willing to accept less than the market price; their opportunity cost was lower than their revenue so they gained from the market.

iii. Examples: In a natural resource case, a dairy farmer might be willing to sell milk at even a very low price because the milk is tough to store and spoils quickly. But in a large market the milk can find a buyer at a decent price so the farmer gets PS. A mine where the ore is near the surface and easily accessible would sell the product even at a very low price. But the market offers a higher price because buyers compete for it, so the existence of the market provides a benefit to the producers.

c. Pareto Improving Trade: a trade that makes both sides better off. If markets allow all Pareto-Improving trades then the market maximizes Total Surplus (= sum of Consumer Surplus plus Producer Surplus)

i. Example from Economist, "Economics Focus: Worth a Hill of Soyabeans," Jan 9, 2010 (also on Blackboard).

d. Deadweight Loss (DWL): a loss that is nobody's gain.

i. Example: Traffic to get over a bridge. Everybody pays a price of lost time and aggravation but this cost is nobody's gain. If everybody paid an equivalent price in money (as a toll) then this cost would be somebody's gain (the government, the public, and/or politicians' cronies).

ii. This is one of the less widely-understood concepts; for example take the voters' dislike to road pricing here in NYC

e.

Price

floor/ceiling effects examples where Total Surplus is smaller &

there is DWL; "Short side rules"

f. Effects of changes in demand or supply

g. Private equilibrium leaves no unexploited opportunities for individuals (no-cash-on-the-table); but might leave opportunities for social action. (See Yoram Bauman, the Stand-up Economist in AIR or on youtube here or here)

h.

Elasticity

allows easy characterization of how changes in demand or supply affect market; is

i. Elasticity works in both directions:

i. if amount supplied were to fall by 10%, what would happen to price?

ii. if price rose by 5%, what would happen to the amount demanded?

|

|

|

On using these Lecture Notes:

We sometimes don't realize the real reason why our good habits work. In the case of taking notes during lecture, this is probably the case. You're not taking notes in order to have some information later. If you took your day's notes, ripped them into shreds, and threw them away, you would still learn the material much better than if you hadn't taken notes.

The process of listening, asking "what are the important things said?," answering this, then writing out the answer in your own words that's what's important!

So even though I give out lecture notes, don't stop taking notes during class. Take notes on podcasts and video lectures, too. Notes are not just a way to capture the fleeting sounds of the knowledge that the instructor said, before the information vanishes. Instead they are a way for your brain to process the information in a more thorough and more profound way. So keep on taking notes, even if it seems ridiculous. The reason for note-taking is to take in the material, put it into your own words, and output it. That's learning. |

|

|

6. More about Consumer Behavior

a. Notate demand for a good, x1 = x1(p1,p2,m), demand depends on price of the good p1, price of other goods p2 (for now just one other good; it keeps down complexity but is generalizable), and budget m

b.

price

rises imply fall in consumption (except for Giffen goods) so generally

c.

can

decompose this change in consumption into income/substitution effects so always

if there is income to compensate for the

change

7. Budget

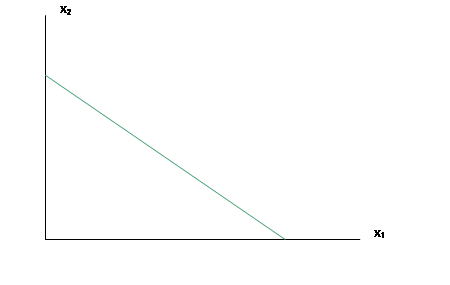

a. Bundles are denoted X, so that a bundle of goods, X=(x1,x2). Typically we take the space of possible bundles to be the real numbers. We can graphically represent these bundles as Cartesian coordinates on an x-y plane. Cases with more than 2 goods are analogous, we just move to higher-dimensional Cartesian space.

b. Assume that the budget set is given by p1x1 + p2x2 ≤ m. (So it can be graphed as bordered by a straight line.)

The

intercept of x1 shows how much x1 could be purchased if the person spent all

her money on just x1; this is . Analogously the intercept of x2 is

.

c. on the budget line, where p1x1 + p2x2 = m, the slope is

(just re-arrange the budget equation to

collect the terms involving x2 and then solve for x2 = …)

d. note effects of an income shift, Δm, a parallel shift of line;

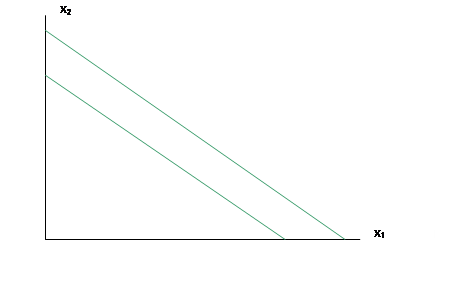

e. effect of price shifts, Δpi, where the new line is no longer parallel and budget rotates around one intercept (the one whose price didn't change). In picture below, a fall in the price of x1 means that more of x1 can be bought if the consumer devotes entire budget to it.

f. and the special case of an equal proportional change in m and all prices so there is no net change

8. Utility

a. From Micro, recall that as long as a consumer's choices satisfy some basic requirements then the choices can be represented by a utility function

b.

Define

Marginal Utility, MU1, MU2 as MU1 = ΔU/Δx1 and MU2 = ΔU/Δx2 (For those with calculus knowledge, then MU1

is the derivative of the utility function with respect to the first argument,

MU1 = and MU2 =

. If you don't know calculus then ignore this

note!)

c.

MRS

=

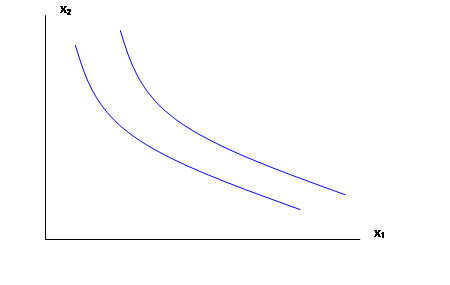

d. So draw indifference curves

9. Choice

a.

Given

and a budget constraint that

b.

we

want to find the goods, x1 and x2, that solve: subject to

.

c.

Usually

optimal point is at a tangency, where or

or

.

d. The last condition is "bang for the buck"

An example from Thomas Friedman's NYTimes column of Sept 15, 2006:

Since the 1970’s oil shocks,

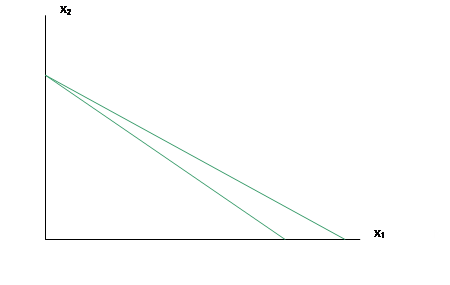

10. Effects of Change in Income

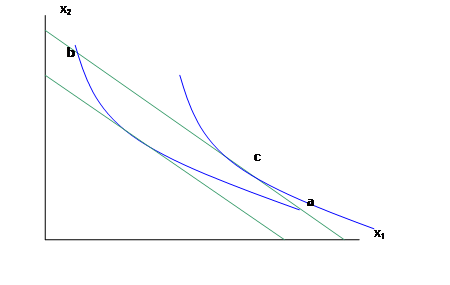

a. As income, m, rises the consumer could buy more of both; can choose any point that is between the intersections of the old indifference curve with the new budget (a and b in the figure below):

or

or

Clearly it is possible that, as income rises, an individual could choose to purchase more of both x1 and x2, or more of x1 and less of x2, or less of x1 and more of x2. It is perfectly reasonable that there are certain goods that people buy less of, as they get richer. Indeed most marketers of consumer goods offer a whole constellation of brands that aim to help people work "up the chain" as they get wealthier. What clothing brands are for poorer (often teen) consumers? For middle-income ones? For the rich?

b. We don't want to limit ourselves to

only certain sorts of goods so we allow the consumer to have this range of

choice. If people buy more of a particular good as they get richer, economists

call this a normal good. Mathematically a normal good, xi, is one

where . An inferior

good, xj, is one where

.

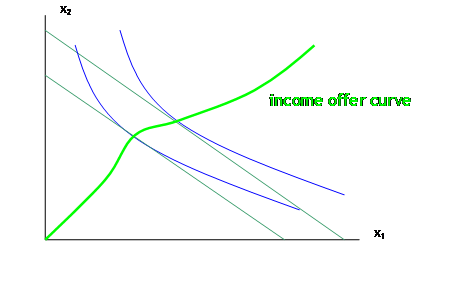

c. Graphically we can plot the income offer curve or income expansion path as showing the bundles of x1 and x2 that the consumer chooses at each level of income:

It is the locus of tangent points of the indifference curves and budget line. Of course it is different for every price combination.

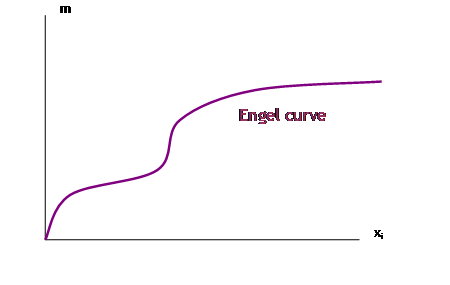

d. We also can consider the Engel curve, which is a plot of the quantity of a good, xi, and the level of income, m (with the dependent variable on the horizontal axis, just to confuse you!).

i. The Engel curve is not always upward-sloping, however. Slopes up only for normal goods.

ii. Inferior goods would have an Engel curve sloping downward. (It's also possible for some goods to be initially normal and then inferior. For instance calorie consumption: in poor societies the richer people are fatter because they can afford not to starve; in rich societies the richer people are more fit because they can afford to exercise and eat better.)

11. Effects of Change in Own Price

a. From and

,

we now consider how the optimal choice of xi

is influenced by changes in its price, pi.

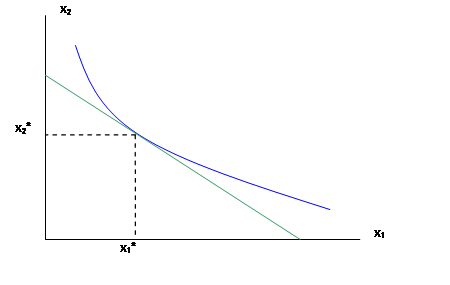

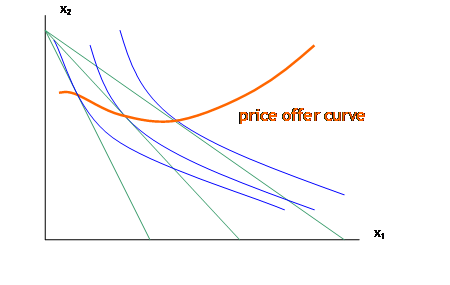

b. Now if we keep income constant but instead change p1, we can observe how the consumer's choice of bundles change. Linking these together gives us the price offer curve:

c. A plot of the price against the amount of the good chosen (again, putting the dependent on the horizontal axis) gives us the demand curve:

12. Cross-Price Effects

a. Finally check the effects of a change

in the price of one good on the consumption of the other good, so . If this cross-price effect is positive then

the goods are substitutes: an increase in the price of one leads consumers to

buy more of the other instead (chicken vs beef). If the cross-price effect is negative then

the goods are complements: an increase in the price of one leads consumers to

cut back purchases of several items (hamburgers and rolls).

13. Individual Demand to Market Demand

a. horizontal sum

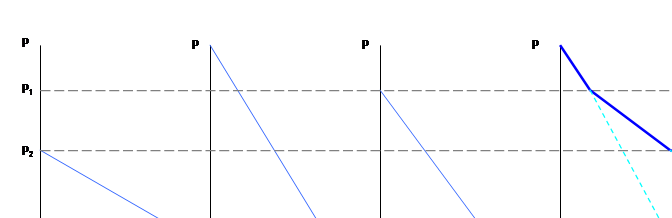

At a quoted price, each person chooses to demand a certain quantity of the good (which might be zero). So if there are 3 people, A, B, and C,

At a price above P1, only person B is in the market, so the market demand is just her demand. At a price lower than P1 but above P2, a reduction in price will prompt both B and C to demand the good. At a price lower than P2, all three people A, B, and C, are in the market. So a reduction in price induces all three to demand more. The market demand curve becomes more elastic since now a fall in price means ΔxA + ΔxB + ΔxC. The market elasticity arises both from intensive changes (each person's demand changes) and extensive changes (people enter or leave the market in response to price changes).

14. Elasticity: when a price rises from p to p', so demand changes from x to x'

a. linear

Linear

elasticity is or

.

b. arc

Arc

elasticity instead uses the average values, and

,

where

and

,

so that

.

c. point

Finally, as

p' and p get closer and closer together (so that x' and x get closer as well),

then the term,  so that the elasticity formula can be written

as

so that the elasticity formula can be written

as (and recall that x is a function of p).

Remember

that elasticity is not constant over a linear demand curve. Since the slope of a line is constant, then is constant but elasticity is this constant

times

,

which is the slope of a ray from the origin to the point under consideration.

15. Example of Choice between alternatives on PPF

Recall from basic microeconomics how we analyzed the choice of an individual facing two desired outcomes. There are some cases where both outcomes are easily achieved; here economics has little to add. There are other cases where there is a trade-off, where progress toward one goal must mean that the other goal becomes farther off.

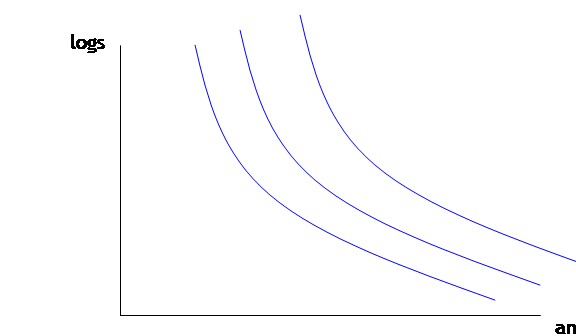

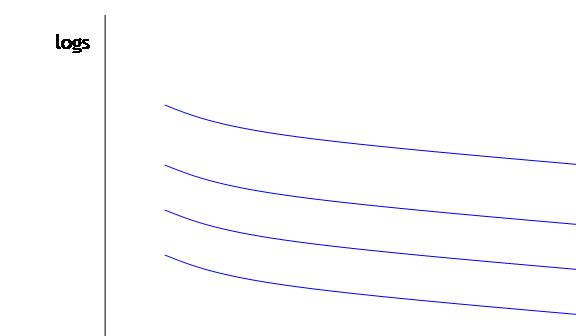

Consider a simple example where we analyze the choices of people who like forests for recreational use (including habitat preservation) as well as for a source of logs (supporting the local economy). We will shorten these two outcomes as "animals" and "logs". People's preferences might look like this:

which implies that this person likes both logs and animals.

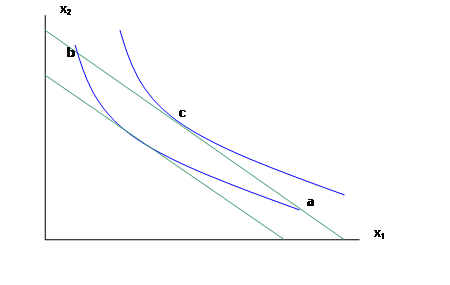

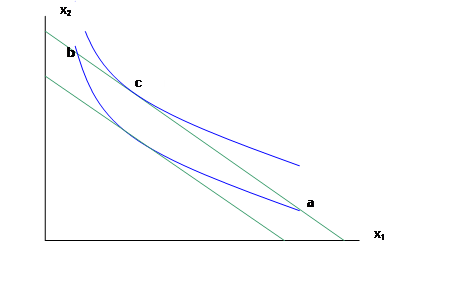

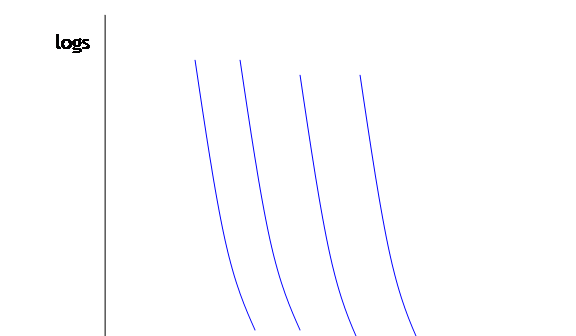

Different people might have different preferences. This person likes animals and cares very little about logs:

While this person cares about logging jobs and not for animals or habitat:

So far we have only discussed what people want. There is another separable component (economic analysis stresses that there is an important separation to be made), which is what is feasible or possible.

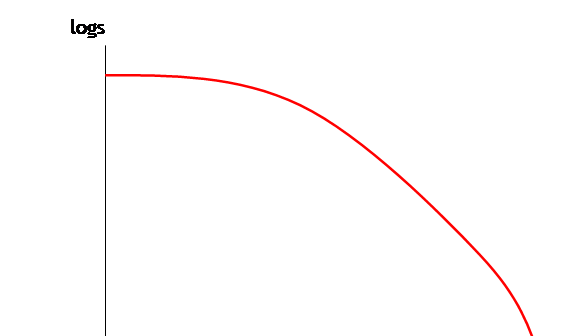

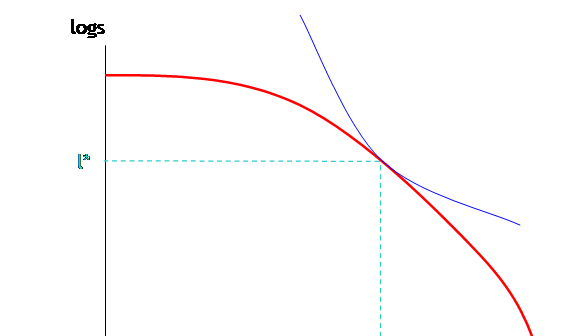

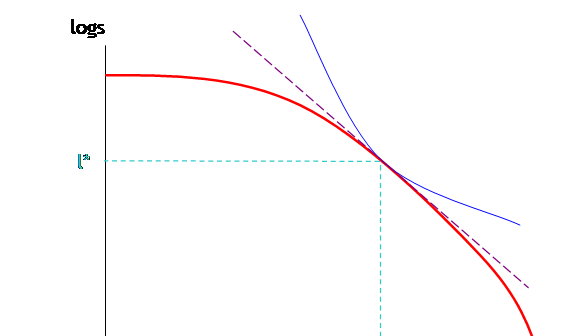

The Production Possibility Frontier (PPF) represents the combinations of the two goods which can possibly be attained. (The PPF shows the maximum; certainly less of both is possible!) While people might wish otherwise, generally there are physical constraints that imply that if, for example, a habitat is entirely devoted to animals (left unspoiled) then it has zero use for logging, and any logging must reduce the habitat value. This PPF could look something like this:

From the PPF we can immediately define the opportunity cost: how much does a completely unspoiled landscape "cost"? The value of the logging which must be foregone. How much does logging "cost"? The value of the habitat spoiled. If choices must be made between the two priorities then every step toward one priority means some diminution of progress to the other priority.

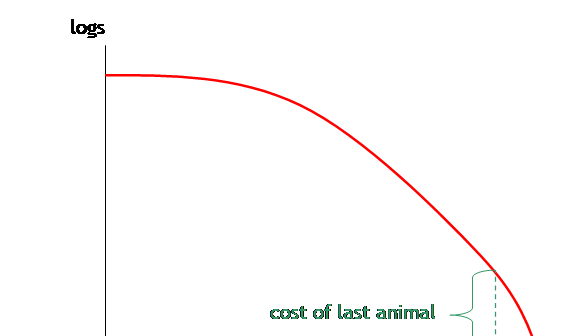

Make the (not entirely serious) assumption that we have some units to measure "animals" and "logs". Starting from a value of zero logs and all animals, suppose we reduced the number of animal units by one? How many more logs could we get? This gives the opportunity cost of the last unit of animals.

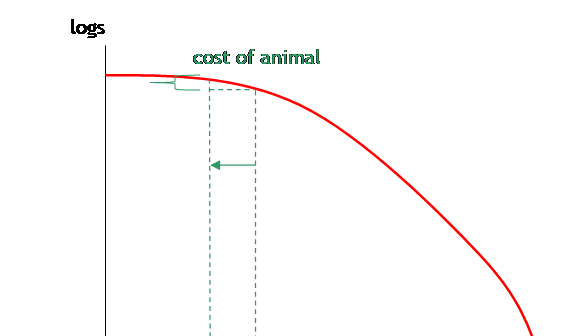

But compare this high cost with the cost (in log units) of reducing the amount of animal, if the amount of animal is already small:

Somehow the society must figure a way to bring these two considerations of production possibilities and utility into equilibrium, to find the tangent where:

A rational maximizing individual who does all of the production by him or herself, and knows his or her own indifference curves, would make this choice. In a world where production and consumption are separated, each side sees only the price,

So producers see only the relative price of a to l but choose optimally; consumers see the relative price and also consume optimally.